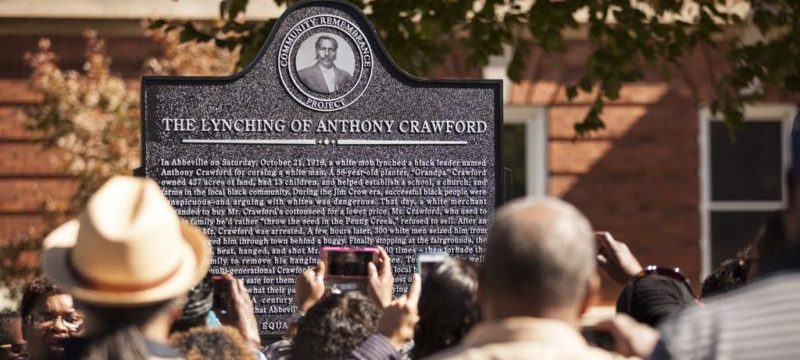

The Lynching of Anthony Crawford

Before the Civil War, South Carolina relied on a plantation economy and enslaved Africans outnumbered white residents. Dehumanized, brutalized, and treated as property, black people resisted in ways small and large to survive. After the Confederacy’s defeat, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution ended slavery and guaranteed black citizenship rights. Reconstruction promised federal enforcement and gave African Americans hope for the future. Black men used their new voting rights and, in South Carolina, elected African-American candidates to all levels of government. African Americans’ political and economic advancement soon sparked resentment and violence. When federal protection ended in 1877, lynching – or murder at the hands of a mob – became a tool for re-establishing white supremacy and terrorizing the black community. White mobs lynched more than 4000 black people in the south between 1877 and 1950, and more than 180 of them were killed in South Carolina. In addition to Anthony Crawford in 1916, at least seven other men were lynched in Abbeville County during the era: Dave Roberts (1882); James Mason (1894); Thomas Watts and John Richards (1895); Allen Pendleton (1905); Will Lozier (1915); and Mark Smith (1919).

In Abbeville on Saturday, October 21, 1916, a white mob lynched a black leader named Anthony Crawford for cursing a white man. A 56-year-old planter, “Grandpa” Crawford owned 427 acres of land, had 13 children, and helped establish a school, a church, and farms in the local black community. During the Jim Crow era, successful black people were conspicuous – and arguing with whites was dangerous. That day, a white merchant demanded to buy Mr. Crawford’s cottonseed for a lower price. Mr. Crawford, who used to tell his family he’d rather “throw the seed in the Penny Creek,” refused to sell. After an argument, Mr. Crawford was arrested. A few hours later, 300 white men seized him from jail and dragged him through town behind a buggy. Finally stopping at the fairgrounds, the mob stabbed, beat, handed, and shot Mr. Crawford over 200 times – then forbade the Crawford family to remove his hanging body from the tree. Terrorized, the well-established, multi-generational Crawford family and many other local black people realized that Abbeville was not safe for them. Amid continued threats, most of the family scattered North, leaving behind what their patriarch had built, and carrying the painful loss of his wisdom and humor. A century later, this maker symbolizes their continued remembrance – and hope that Abbeville never forget or repeat that horrendous October day.

This historical marker was sponsored by the Equal Justice Initiative in 2016.